Flour Mill: An Overview

Edited by: www.immy.cn / www.immyhitech.com

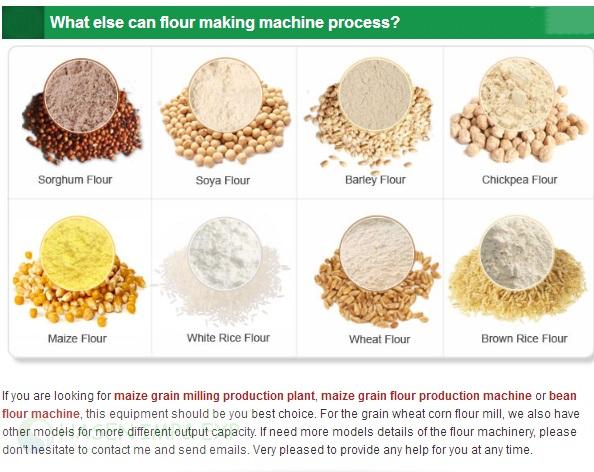

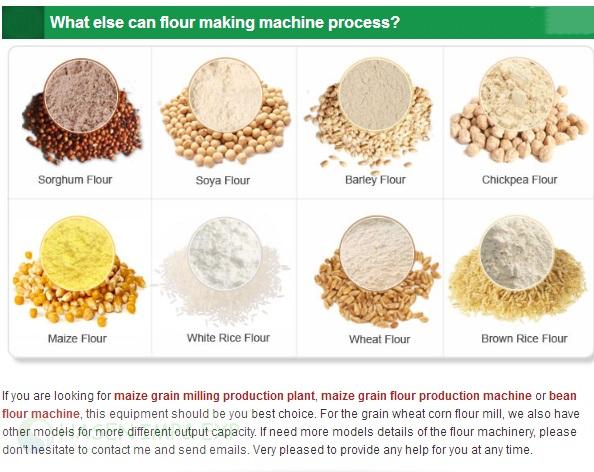

Flour mills are industrial facilities designed to transform cereal grains—primarily wheat, but also corn, rice, barley, and rye—into flour, a staple ingredient in global food systems. From small-scale artisanal operations to large-scale industrial complexes, flour mills play a critical role in connecting agriculture to food production. This overview explores their history, types, processing workflows, key equipment, quality control measures, applications, and emerging trends.

A flour mill is a facility where grains are cleaned, processed, and ground into flour—a fine powder used in baking, cooking, and various industrial applications. The practice of milling dates back millennia, with early civilizations using manual tools like stone mills (e.g., ancient Egyptian querns or Roman mola) powered by humans, animals, or water.

Ancient Origins: Early mills relied on stone grinding surfaces (upper and lower stones) to crush grains. Water-powered mills emerged in the Roman Empire, followed by windmills in medieval Europe, revolutionizing grain processing by scaling production.

Industrial Revolution: The 18th–19th centuries brought mechanization: steam power replaced manual labor, and roller mills (invented in the 1870s) replaced stone mills, enabling more precise grinding and higher yields.

Modern Era: Today’s mills are highly automated, using electricity, computerized controls, and advanced machinery to optimize efficiency, consistency, and safety.

Flour mills vary by scale, purpose, and grain type. Common classifications include:

Small-Scale/Artisanal Mills:

Serve local communities or specialty markets.

Often use traditional stone mills for "whole grain" or organic flour.

Capacity: Typically 1–50 tons of grain per day.

Medium-Scale Commercial Mills:

Supply regional food manufacturers, bakeries, and retailers.

Balance automation with flexibility to produce multiple flour types (e.g., all-purpose, bread flour).

Capacity: 50–500 tons per day.

Large-Scale Industrial Mills:

Operate at national or global scales, supplying large food corporations.

Fully automated, with integrated systems for cleaning, grinding, and packaging.

Capacity: 500+ tons per day; some mega-mills process over 10,000 tons daily.

Specialty Mills:

Focus on specific grains (e.g., gluten-free oats, spelt) or processes (e.g., organic, heritage grain milling).

The journey from grain to flour involves several critical steps, each designed to ensure purity, texture, and quality:

Inspection: Grains are tested for moisture content, protein levels, and impurities (e.g., stones, weeds, broken kernels) upon arrival.

Cleaning:

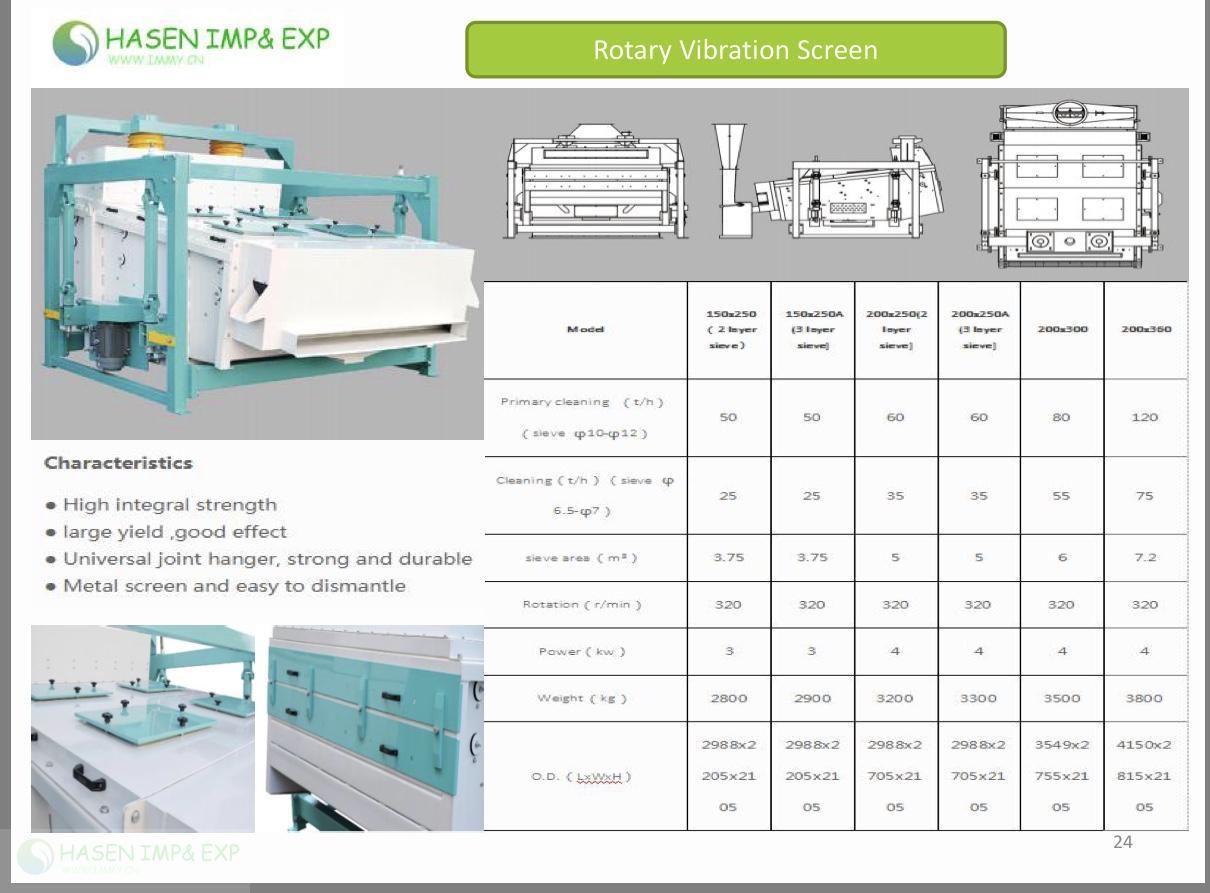

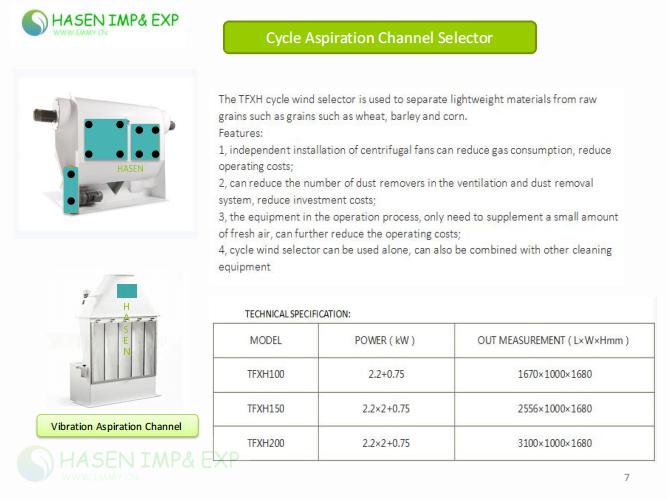

Screening: Vibrating screens remove large debris.

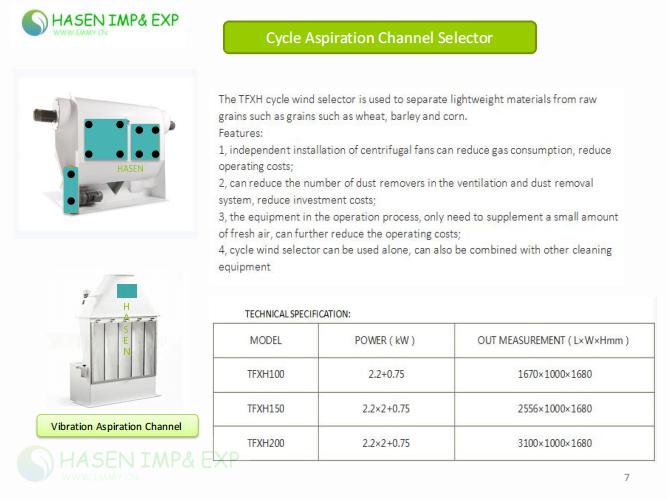

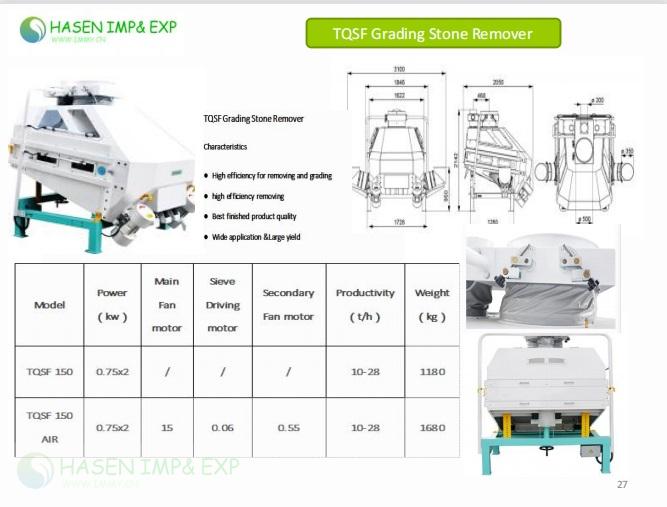

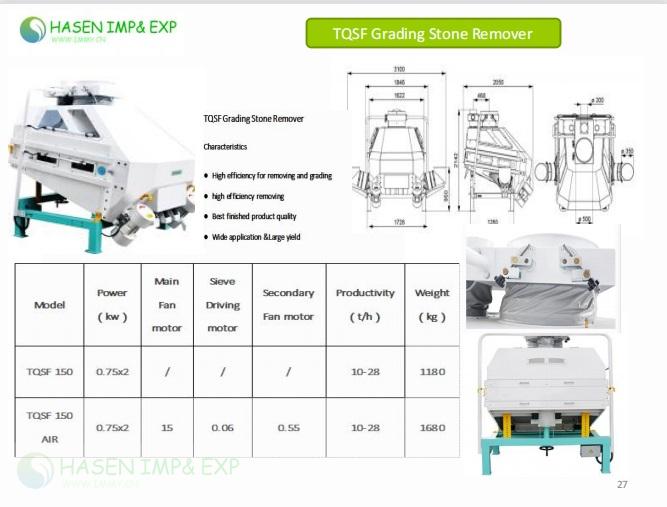

Destoning: Gravity separators or aspirators separate stones (denser than grain).

Magnetic Separation: Magnets remove metal fragments.

Scouring: Brushes or air jets remove dust, chaff, or outer husks.

Grains are adjusted to optimal moisture levels (typically 14–16% for wheat) to:

The cleaned, conditioned grain is crushed and ground to separate components and produce flour:

First Break: Grains are cracked into coarse particles using roller mills (steel cylinders with grooved surfaces) or stone mills.

Sieving (Purification): Coarse particles pass through sieves to separate bran and germ from endosperm fragments.

Subsequent Reductions: Endosperm fragments are re-ground in multiple stages (e.g., "second break," "reduction rolls") to produce finer flour. Stone mills grind grains more slowly, preserving nutrients but yielding coarser textures.

Blending: Different flour grades (e.g., high-protein "strong" flour for bread, low-protein "weak" flour for cakes) are mixed to meet specific specifications.

Aging/Bleaching: Some flours undergo aging (natural oxidation) or bleaching (with agents like benzoyl peroxide) to whiten color and improve baking properties.

Enrichment: In many regions, flour is fortified with vitamins (e.g., B vitamins) and minerals (e.g., iron) to address nutritional deficiencies.

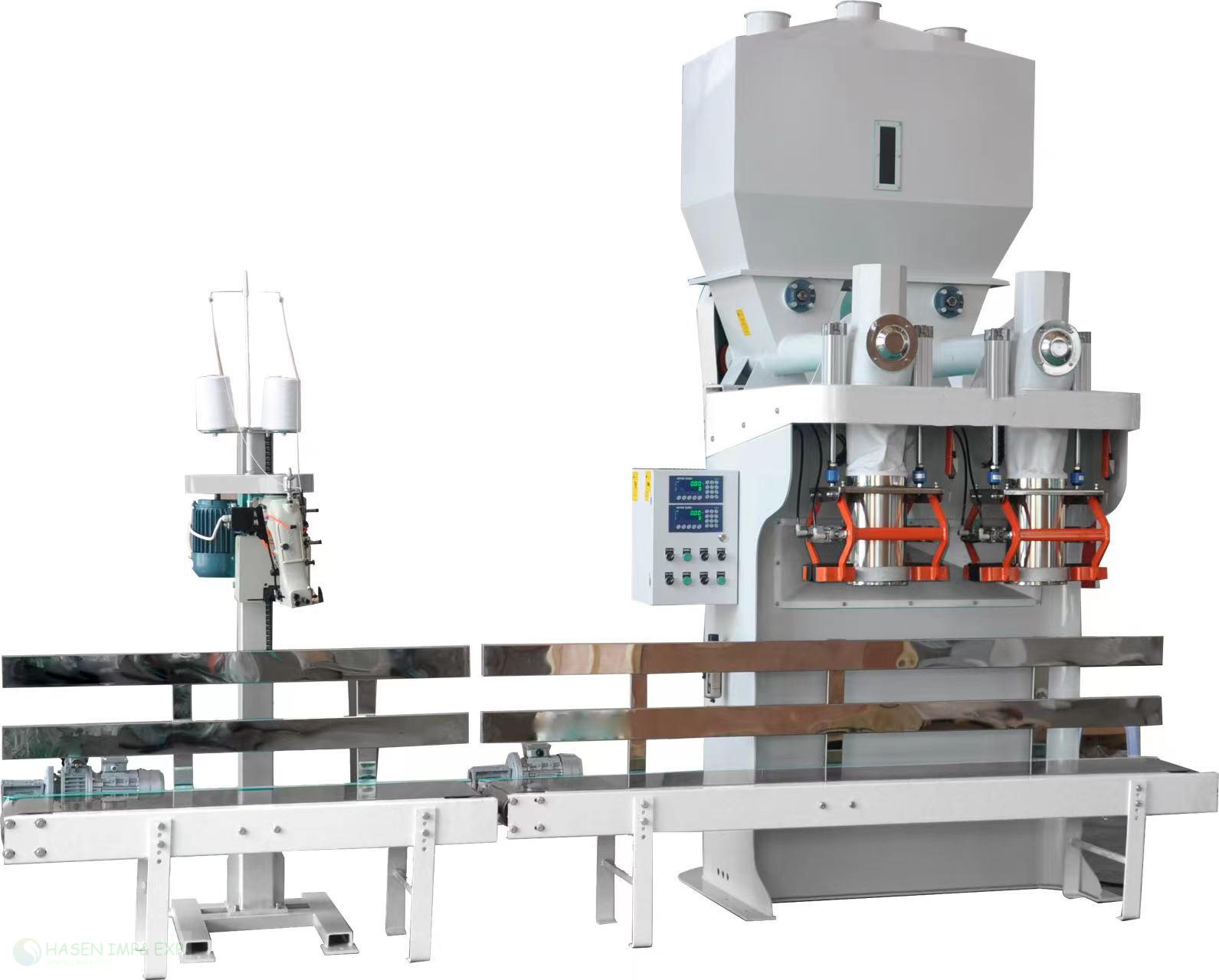

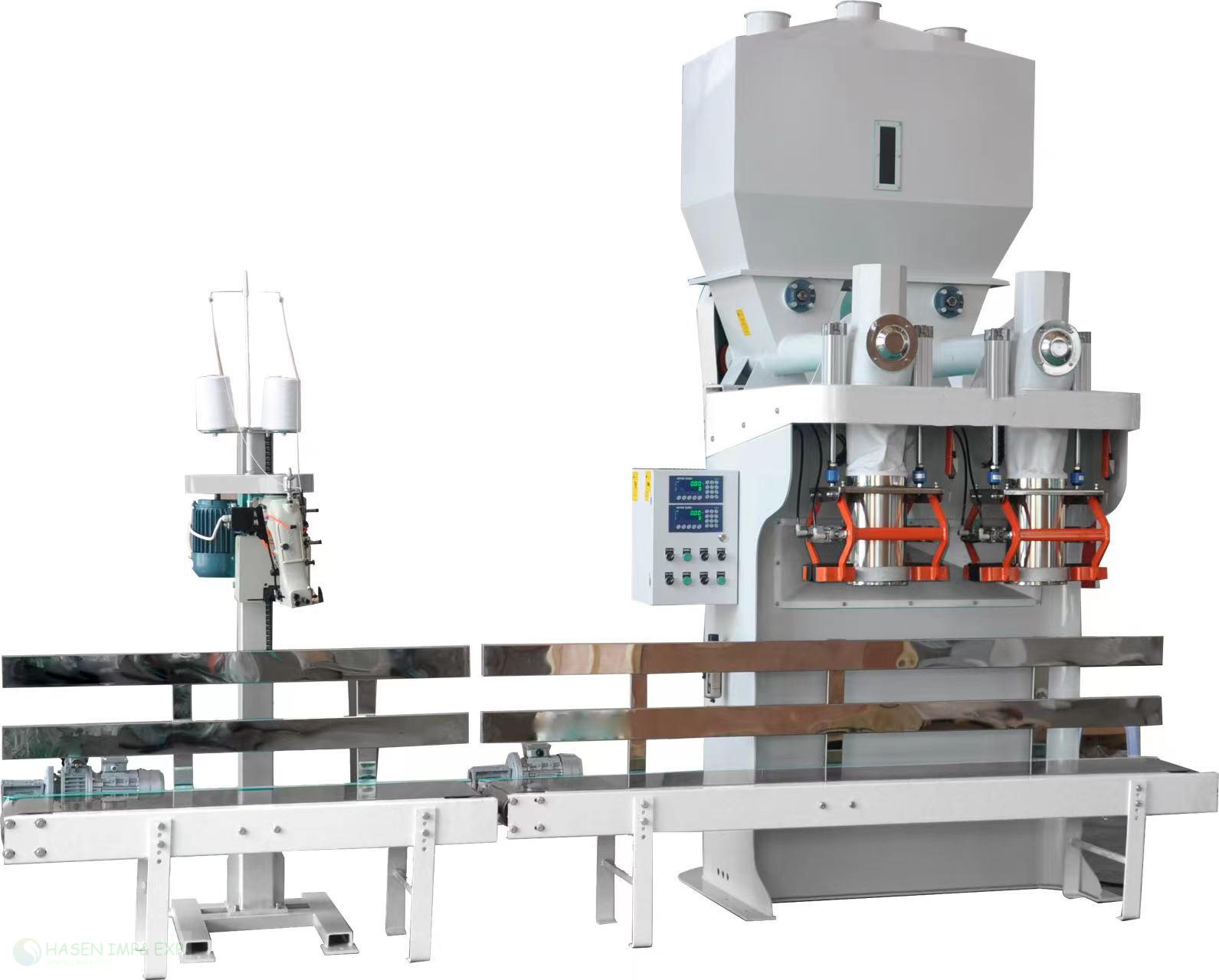

Flour is sifted to remove lumps, then packaged in bags (2–50 kg) or bulk containers. It is stored in cool, dry silos or warehouses to prevent moisture absorption and spoilage.

Cleaning Equipment: Vibrating screens, destoners, magnetic separators, and scourers.

Conditioning Tanks: Insulated vessels for controlled moisture adjustment.

Grinding Machinery:

Roller Mills: Most common in industrial settings; paired steel rollers with adjustable gaps to control particle size.

Stone Mills: Traditional, slow-grinding stones (e.g., granite) for artisanal or whole-grain flour.

Sieving Equipment: Plansifters (multi-layered screens) or purifiers (air-assisted sieves) to separate bran and germ.

Blending Machines: Ribbon blenders or paddle mixers for uniform flour mixing.

Packaging Lines: Automated weighers, baggers, and sealers for efficient packaging.

Consistency and safety are paramount in flour milling. Key measures include:

Raw Material Testing: Grains are analyzed for moisture, protein, mycotoxins (e.g., aflatoxins), and pesticide residues.

In-Process Monitoring: Sensors track grinding temperature, particle size distribution, and moisture to avoid overheating (which degrades nutrients) or clumping.

Finished Product Testing: Flour is tested for:

Ash Content (indicates bran contamination; lower ash = whiter flour).

Gluten Content (critical for baking properties).

Microbial Load (e.g., bacteria, mold) to ensure food safety.

Regulatory Compliance: Mills adhere to standards like the FDA’s Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMPs) or the EU’s Food Safety Authority (EFSA) guidelines, often implementing HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) systems.

Flour is a versatile ingredient with applications across industries:

Food Industry:

Baked goods (bread, pastries, cookies).

Pasta, noodles, and couscous.

Batter and breading for fried foods.

Baby food and cereals.

Non-Food Uses:

Animal feed (by-products like bran or germ).

Biodegradable packaging (starch-based materials).

Ethanol production (from corn flour).

The industry is evolving to meet sustainability, health, and efficiency demands:

Flour mills are indispensable links in the global food chain, transforming raw grains into a foundational ingredient. From ancient stone querns to high-tech industrial complexes, their evolution reflects advances in technology, nutrition, and sustainability. As consumer demands for quality, transparency, and sustainability grow, the industry continues to innovate, ensuring flour remains a staple for generations to come.

We do hope to be your valued supplier of flour mill turnkey project provider from design, manufacturer, commissioning of project from China